When our dictionaries arrived a few short months ago, it was into a different world. I am comforted that every child has one, and we have set tasks to help students reflect on the vocabulary they have been taught. My sincere hope is that the dictionary still achieves what we set out for it to do, and helps to close the vocabulary gap. It doesn’t require IT access to read, and even some of our hardest to reach students made sure they had one to go home with when we closed. There is a danger, however, that like all the home learning tasks we set up, they will be disproportionately accessed and the gap will widen. Towards the end of this post I have outlined ways in which it can be used in classrooms in September to ensure that those furthest behind can be supported to catch up with their peers.

I am sharing this post now, as many schools turn their attention towards improving their curricula ready for September. A strong focus on explicit vocabulary teaching is likely to form a part of that, and this project may be one that, depending on how schools have set up their remote learning, could be realistically achieved during these lockdown hours.

Our TA Dictionary is very much a collaborative effort; an attempt to give our young people access to the tier 2 and 3 vocabulary that they need in order to be successful within all their subjects across the curriculum, it contains over 1200 words, definitions, and etymological origins.

Purpose

I was given the ‘vocabulary project’ by our principal @stevemargetts, who, in collaboration with our head of English @jenbrimming came up with the idea that we should have ‘a book of all the words’ our young people needed to be able to access their subjects across the curriculum. We had all been influenced by @doug_lemov’s Reading Reconsidered and Alex Quigley’s (@HuntingEnglish) ‘Closing the Vocabulary Gap’. Jen had also been an examiner for GCSE Literature, and had been struck by the way in which a candidate would immediately position themselves as likely to obtain the highest bands through their selection of appropriate and useful vocabulary. It can be very difficult to pin down exactly what gives the ‘flair’ and ‘cogency’ of those maximum mark answers, but there is one thing they all share and that is wide, appropriately selected, vocabulary.

The context of Torquay Academy is one in which we must do everything we can to provide our young people with the ‘equipment they need to climb the curriculum mountain’, a topic I have blogged about previously here. Explicit vocabulary teaching has been recently highlighted by the EEF as the second most effective method of improving literacy within schools, second only to disciplinary literacy (although I would argue explicit vocabulary teaching forms part of disciplinary literacy). This report provides heartening evidence that we are adopting measures that are likely to have the most impact.

Background – Word of the Week

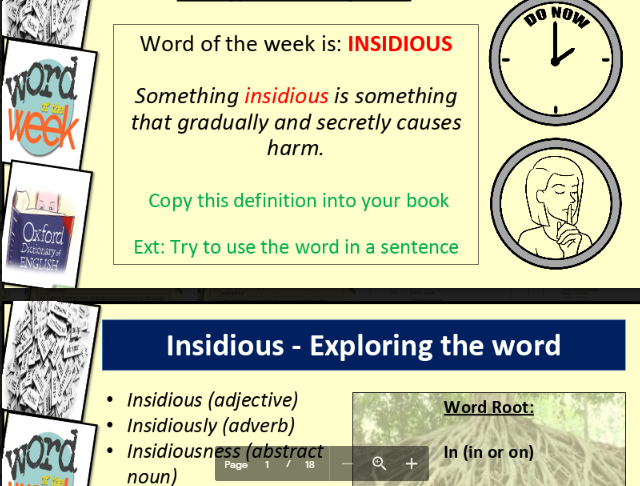

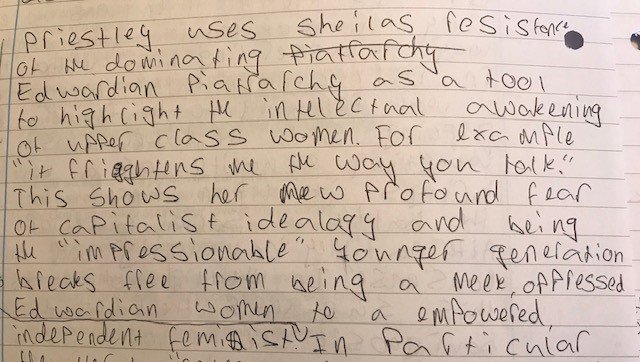

Within English, Jen had already introduced the ‘Word of the Week’ following the explicit vocabulary model set out by Lemov in Reading Reconsidered. She has tweeted the folder with the template here along with student examples that might be useful for CPD. Below I have deliberately chosen the work of a child who had previously struggled with written expression.

The Word of the Week/Day concept is nothing new, but the reason it can often fail to have an impact is, as is often the case, down to implementation. To ensure explicit vocabulary teaching is embedded and results in young people using it effectively, we have found the following has worked for us:

- Map Words of the Week systematically alongside the curriculum. Importantly, it is not words which allow students to unlock factual information that are necessarily important, such as ‘suffragette’ when teaching an Inspector Calls. It is more the vocabulary which allows young people to express ideas surrounding the text. So rather than ‘suffragette’, it is more useful for students to understand ’emancipation’. This term can also be more universally applied to other texts.

- Vocabulary must be interwoven with the teaching within that week, and revisited repeatedly with regular opportunities to practise using the word. So along with the initial 15 minute explicit teaching episode at the start of the week, the word must also be important within the curriculum for that week.

- New vocabulary should be applied backwards as well as forwards, often bringing new understanding to a previously taught text/concept. 5-a-day retrieval questions can be carefully planned to balance recap with new new knowledge.

- Students need to have access to material they can access independently so that they can refer to these key terms and recap their learning. Our homework is based around knowledge organisers which contain this information, but as these are produced each cycle they can be perceived as being ‘done’ once a cycle is over. The idea of the dictionary is to keep the learning relevant throughout their school careers.

- Practice can be oral as well as written. Some carefully targeted cold calling can help to build young people’s confidence in showing off their mastery of a new word, and the knock-on impact of this feeling of ‘cleverness’ in front of the class cannot be underestimated. By the time they reach year 11 and have used and revisited the word ’emasculation’ repeatedly, they feel that they have something genuinely intelligent to say about Lady Macbeth – and they are right to feel that way.

Alongside other strategies, introducing the word of the week at TA has been central to the steep improvement in student progress in English. It has therefore thankfully not been a very difficult ‘sell’ to the rest of the school.

It is fair to say that, particularly with the introduction of knowledge organisers in 2015, most subjects had a good handle on their key vocabulary already. Some have already gone down the ‘word of the week’ route, others are making a much more conscious effort to explicitly teach vocabulary, others still were already systematically teaching vocabulary very effectively because that is what great teachers with access to well structured curricula do.

Producing the dictionary

The different stages of the project were as follows:

- Identify the vocabulary terms for each subject for each cycle and year group.

- Come up with an appropriate layout/format/organisation.

- Write the pages in collaboration with department areas to ensure accuracy.

- Produce an index of all of all terms and where they could be found.

- Work with publishers to produce final design/front cover/binding.

- Decide on practical uses for the dictionary.

- Identifying the terms

The fact that knowledge organisers were already in place made identifying the key words much easier as many subjects had either designed a ‘key vocabulary’ section, or it was easy to pull out the words from the knowledge organisers themselves.

Different subject areas had varying levels of involvement in producing the pages. English and MFL wrote their own pages. @johnemellitt’s science team came up with a ‘Science word bank’ which cut across year groups and cycles and contained what they felt were the essential concepts. They provided the terms, and the ‘vocabulary team’ (a small team of dedicated English teachers) wrote up the definitions which were checked back with the subject specialists. For a small number of subjects I found their knowledge organisers, pulled out what looked to be the key terms and then ran the finished pages passed them when they were done.

2. Coming up with the layout/design/organisation

The first draft of the dictionary was organised into year groups and cycles, the idea being that students could make links between their learning in different curriculum areas. However, feedback from students has been that they would prefer to have each subject grouped together. This is because they tend to use the dictionary when they are writing about a topic, and they would find it useful to be able to access either prior learning or more advanced learning to support their understanding and expression. The second draft will also have a small ‘tab’ on the side of the page to make it easier to find when flicking through.

The English pages looked like this:

This page is essentially a snapshot of the explicit vocabulary teaching slides students have been taught. Initially, the plan was to include the box you can see which connects the root of the word to other words they have been taught elsewhere in the curriculum. However, many, many, many hours of writing dictionary pages later, it became obvious that this was not going to be sustainable to produce alongside teaching. The index does provide a useful place for students to see at a glance where the same word comes up more than once in their school careers, and often seeing that vocabulary in the different contexts, with subtly different meanings, helps to cement their understanding.

It also became apparent that we were not going to have enough space for all pages to mimic the English style, so these look like this in the first draft:

One of the key aspects of the dictionary was the etymology of the words. It is important that students have strategies to work out what unfamiliar words mean, and is the central reason why the GL Assessment found that it was far more challenging for students to access English Language papers and those from a variety of other subjects than it was to access the English Literature paper. With literature, students are mainly given material they have encountered before, with a teacher to guide them through. It is also not essential for them to understand all the words on the paper – they just need enough of a spring board from which they can launch their understanding of a character or theme.

We took screen shots of the etymology from google, but looking at the final printed version they were of variable quality. It also did not feel that the etymology was foregrounded enough. Alongside the dictionary production, our amazing SEN department (specifically Carol Rowan) began producing displays of each of the key words:

I was a bit slow on the uptake, but I realised that our next dictionary draft just needed to incorperate all of this amazing work. So the next version will look more like this (we are still in the drafting phase):

We had a page of common roots/prefixes/suffixes in the first draft, but going through this process with the second draft means that we will be able to expand this to be much more comprehensive.

3. Writing the pages and ensuring accuracy

As explained above, both English and MFL wrote their own pages. For the others, a small team of English teachers including @MissJ_English wrote the pages for all of the other subjects in their own time. This is the part that I think schools will need to balance carefully if they undertake a similar project. A central belief that our young people deserved this book drove this small team to voluntarily give up their time to produce it. Staff should not be expected to produce pages for their department areas unless they are happy to do so, or have been given adequate time to get the work done. As explained earlier, perhaps this lockdown will give school leaders the opportunity to work on projects such as these with the aim of closing the vocabulary gap in September. The pages were created in google slides, and shared with the appropriate departments to check before they were sent to the publishers.

4. Producing an index

This was one of the hardest parts of the book to write. All of the terms had been saved into a central google document divided into different boxes for each subject, year group and cycle. The terms needed to be alphabetised with the subject, cycle and year group recorded next to it. I ended up with 11 pages that look like this:

The fact that it was really interesting kept me from going slightly nuts as words were changed or the order they were taught changed. We were lucky enough to have several days INSET for curriculum improvement at the end of last year, so that inevitably ended up with whole scale changes to a number of subjects. I completely understood the need for changes, it was great that everyone was engaged with getting it right – it just made it really difficult to look up, replace and re-alphabetise. So lesson learned – create the index as the very, very last job!

What made the index so interesting was finding the commonalities across subjects. The number of terms that are taught in RS and history that we also teach in English was something that was unsuprising, but to pinpoint exactly which concepts were taught when was really useful. I am keen for us to go as far as recycling resources to make accessing prior knowledge even more straightforward, and the INSET we ran in September suggested the dictionary as a resource for teachers as well as students when planning lessons. In the past there has been a tendency to keep resources locked away, a sense that if they are ‘done’, then that’s it, their usefulness is exhausted. I think the opposite is true – not for entire lessons, but for key slides/extracts/worksheets. Linking prior learning to new learning in a way that builds confidence and familiarity can only be a good thing, particularly for our disadvantaged students.

5. Work with publishers

We have built up a relationship with a supplier who creates all of our exercise books and revision materials. The dictionary was an extension to this, but one which turned out to be quite complex. There were a number of different files which needed organising in a very specific way, and communication was not always straightforward. The number of pages also exceeded the usual maximum for the type of binding we use, so it needed to be sent to a separate binding company. It is fair to say that this was the bumpiest part of the road, but again, lots of lessons learned for next time.

6. Come up with practical uses in the classroom

The following were the main ways in which we envisaged the dictionary being used within the classroom, but we were very much in the early days of this when the schools closed:

- To support delivery of Word of the Week (students could look up the word and use it to refer back to if the teacher was going to quickly for them/they arrived late).

- During the 5-a-day retrieval practice. As lots of this links back to previous vocabulary going back years on occasion, the dictionary provides a useful reference for ‘no opt out’.

- During ‘superteaching’ (this is our week following assessment week) to support redrafting. Similarly within ‘purple pen’ lessons once students have received formative feedback on mid-point assessments.

- When essay planning and preparing for assessments.

- In reading lessons (once per fortnight for KS3) as part of the Do Now (which is creative writing following reading an extract).

- For homework alongside their knowledge organiser/assessment preparation.

- For homework alongside the Reading Journals (they complete on Frayer model per week).

- To support the use of Frayer models (some subjects were already using these):

The practical uses section is one I plan to revisit again in the new year as we hopefully get more feedback from students and teachers regarding how they have used it.

If anyone has any ideas on what could be incorporated into the second draft, or how the dictionary could be used I would love to hear them.

I’ve since published the word bank for the dictionary, along with other disciplinary literacy ideas here: